COVID-19 Communications

May 8, 2020

McGovern College Students:

Here's an update for May 8, 2020, with three topics: spring 2020 grades and the necessary decisions you must make; financial resources for students, artists, and organizations; and an open letter to graduating students.

Note that I have continued to receive questions via email and I have continued to answer these. If for some reason you have sent me a question and have not received an answer, first let me apologize, and second let me invite you to resend the question to me directly so that I have an opportunity to address it.

Spring 2020 grades

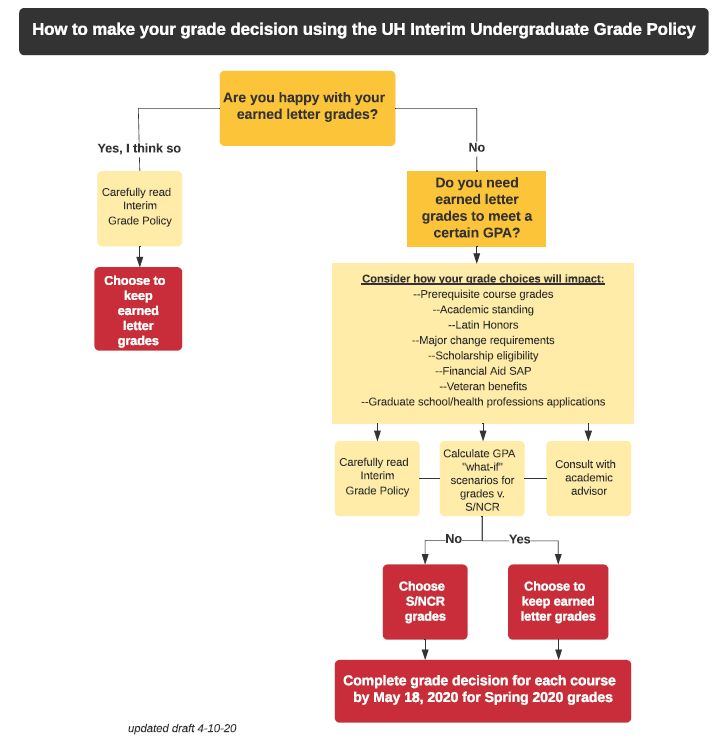

We have now passed the last day of class for spring semester 2020 and are approaching the May 18 deadline for decisions on grades in your courses. Please recall the interim graduate and undergraduate grade policies posted earlier this semester by the Provost's office. To help you make decisions on how to proceed with grades, please also refer to this decision tree:

Financial resources for students, artists, and organizations

I have been receiving questions on financial resources available to students, especially graduating students, during this difficult time. Many of you are also independent artists, and many of you work for or with the independent non-profit arts organizations that are so important to the arts ecosystem in the city of Houston. All of these sectors have been significantly impacted by the public health crisis.

In an effort to keep you fully informed, and knowing that not all of this information will apply to everyone reading these updates, I direct you to the following information:

- the University of Houston's Cougar Emergency Fund and Office of Financial Aid, both of which offer pathways for assistance. The Cougar Emergency Fund provides relief in the form of small grants; the Office of Financial Aid is taking requests for re-evaluation of financial aid packages. More information and application information is available from the Office of Financial Aid.

- this summary list of financial resources that we (in the McGovern College) compiled last month

- this guide to options for help for arts organizations, published by the Houston Arts Alliance, with the help of a city-wide coalition of arts organizations of which the McGovern College of the Arts is a participant

- this guide to options for help for individual artists, also published by the Houston Arts Alliance with the help of the city-wide arts coalition

- this resource list, from a May 8 town hall meeting organized by Houston Arts Alliance and the city-wide arts coalition

- the Houston Arts Alliance's Disaster Resilience for Artists & Non-Profits page, where a great deal more information is available

Open letter to graduating students

I've been thinking about our graduating students often this week. Our commencement ceremony was to have been this past Wednesday night, before we were forced to postpone. I feel for every one of you who were looking forward to walking across that stage. I missed shaking your hand at that moment just as much as you missed having the opportunity to walk. I look forward to the day--and it will come--that you get to walk and I get to shake your hand and congratulate you.

President Khator released a recorded message to students this week. If you missed it, you can view it online here. I also released a message specifically for McGovern College students; you can view it online here.

Our keynote speaker at commencement this year was to have been the immediate past chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts, Jane Chu. I normally would also have delivered short remarks as well. My remarks usually focus on the values that I hold and that I want to pass on to you as you leave the university and embark on a career.

In lieu of being able to make remarks this year, I have chosen instead to post a transcript of remarks that I made at our commencement exercises last fall in the Cullen Performance Hall. Here's a pdf copy, and the complete text follows below; I'll then follow the text with some concluding thoughts on our current situation:

on the occasion of spring commencement, May 6, 2020

[transcript of remarks delivered at McGovern College of the Arts

commencement exercises, December 12, 2019]

These remarks address our graduating students, with an awareness that the message here might be of broader interest as well. I would like to talk to our students specifically about your education in the arts: about why you got that education, about the value of that education, and about what you might do with that education.

I would imagine that most of you might have pursued your education in the arts for the same reason that I and many of my colleagues pursued it. Perhaps you did it because you found inspiration in the arts. Perhaps you did it because you found in the arts answers to some of the hard questions, some of the unanswerable questions, that you had been asking about your life and your world. Or maybe you found in the arts not the answers, but rather questions themselves: maybe the arts were an avenue, as they are for many of us, through which you could articulate the questions that you thought needed to be answered—whereas without the arts, or outside the arts, you might not even have known what questions to ask.

This phenomenon or this experience might resonate with many of us because the arts, and the artists who make them, are among those in our society who are the most comfortable asking the most uncomfortable questions. The arts, and artists, are among those who are the most comfortable at solving the most intractable problems that we face in the world today. Whereas much of the world sees all issues—all problems and all solutions—in clear shades of black and white, artists see these same issues, this same world, in rich tones of gray—on a spectrum of complexity—in complex colors that, I would venture to say, all of us know are out there, but few of us are comfortable enough to admit seeing them. The arts are an avenue to becoming comfortable with discomfort, to becoming comfortable with the reality that not every question has an easy answer that you might want to hear.

This is the source of much of the value in an arts education. But let’s think a bit more deeply about this question of value. I find that this is a question that’s often misunderstood—especially in today’s environment, in which we find higher education under a kind of assault. This is an assault that some will say we have never seen, but the reality is that it has occurred before, including around the middle of the nineteenth century, around the time of the birth of the modern research university. The questions of value then were similar to the questions of value we face now, and in our case, in the arts, we would do well to draw a connection between these questions of value for higher education in general and similar questions of value for arts education in particular.

The value of an education in the arts is something like the value of higher education itself. Higher education is not exclusively about “educating for job skills” or “educating for the workforce.” It is just as much about educating for citizenry—that is, educating to create complete citizens in today’s society. In higher education, and in the arts, we educate for democracy. Higher education is a search for truth; it is an avenue toward enlightenment that is critical if our citizenry is to find meaning, value, and purpose in a life of service to their democratic society. We believe this value, furthermore, to be widely applicable, to people of all backgrounds and all career trajectories: higher education is a public good, access to which the public university has an obligation to protect. Just as much as you, our students, are obligated to avail yourself of the higher education that has been made possible for you—whether through the generosity of your family, through scholarship support, or through your own toil and efforts—we in the university are just as much obligated to protect its value and keep higher education from becoming a private and privileged commodity accessible only to a select few. Thomas Jefferson was afraid of enabling the rise of what he called an “unnatural aristocracy”—one based on birth, wealth, and privilege rather than on merit, intellectual talent, and the ability for critical thinking and reasoning. Our buying into, our accepting without question, our society’s rhetoric—so common today—that higher education, or an education in the arts, is a privilege only for an elite few is as sure a way as any to set off down the path toward that unnatural aristocracy.

Related to this question of value is one that I know all of your families are interested in: just what are you going to do with that arts education that you just completed? This is in many ways the most important question. But I’m not going to pretend to try to answer it in the way you might expect. Rather, I see this as one of those questions that must be answered in slightly varying shades of gray rather than in clear black and white. That’s because I think that to revert to talking only about what job you’re going to get with your education—only about job skills and nothing else—is to risk undermining the value that we just established for that education. Many commentators have addressed this topic, but their voices may not be as prominent as some others in the national dialogue. Lynn Pasquerella, president of the Phi Beta Kappa Society, tells us, for example, that the real purpose of higher education—educating for a search for truth, for a search for enlightenment, and for democracy—is hard to reconcile with what she calls the “rhetoric for hire” and the “return on investment narrative” that we hear so often today. The narrative she’s referring to is one that has you making a rather simplistic trade of tuition in exchange for employment and income. But this is a false narrative: money and employability cannot be the lone metric for determining the value of higher education, just like economic impact cannot be the lone metric—or even the most important metric—for determining the value of the arts in a society. Just because it’s harder to quantify with a clear dollar value the work that artists do, and the products that artists produce, doesn't mean that that work and those products are not valuable in our culture and our society. If you believe this, then you have lost sight of the very purpose and value of the arts—and, indeed, the very purpose and value of education, in its enabling you to function fully as productive, contributing citizens of your society. That purpose alone is a worthwhile investment of money and a worthwhile outcome for which one invests tuition dollars.

So this is what you are going to “do” with your education. I know very well that everyone graduating today is not going to make a career as an artist. Not everyone is going to make a living as a professional in the arts discipline in which you trained. However—and this is very important—this is not a failure. You have not failed, nor has the institution failed you, as long as you use your education for the purpose that it truly serves. Protect its true value. We—your university—have an obligation to protect the value of higher education by making education relevant for you. Cathy Davidson, of the City University of New York and formerly of Duke, recently wrote a book on higher education reform in which she makes a case for a relevant education that includes opportunities for internships, apprenticeships, service learning; opportunities for connecting the work you’re doing in the classroom with an impact in the community around you; opportunities for meaningful first-year experiences and equally meaningful capstone experiences; and opportunities for collaboration across disciplines, where those disciplinary silos into which the university is so neatly carved up are not individual ivory towers for learning but rather are “different approaches to the same enlightened end.”

We have that obligation, yes; but you also have an obligation, one that you are acquiring by virtue of your graduating from an institution of higher education. You have an obligation to protect higher education by using your education as a platform from which to become an advocate for its value. Do not leave the university and sink to the level of those who would assault its purpose. If your education wasn’t perfect, then join us in making it better; become that productive citizen who values access to education as a means of improving and elevating our society, our collective rhetoric, and our democratic processes. Above all, protect the value of the arts: it is your responsibility to explain to our society the value of the arts and of your education in the arts. You must not let those around you, including those in the political class, take the easy way out and make the facile argument, or perpetuate the fallacy, that money and economic metrics are the sole determinant of value or that the STEM disciplines are somehow more valuable than the arts disciplines simply because it is easier to measure their impact in dollar values.

That is what you will “do” with your arts education. No matter what profession you pursue, no matter what career trajectory you end up on, remember that this is your responsibility, your obligation: protect the value of higher education; protect the value of the art forms in which you initially found inspiration, in which you found questions, and in which you found answers. Don’t forget where the real value of education and the real value of the arts is to be found; don’t take the easy way out. Join me in ensuring that my generation, your generation, and your children’s generation create a world in which education and the arts are among the most valuable assets in a great society. That is a world of which we will be proud, and that is a world in which we will want to live.

Thank you and congratulations to every one of you.

I recognize that this is an extraordinarily difficult environment into which you have graduated. None of us would have chosen this for you, here at the beginning of your professional careers. At the same time, I think that now more than ever, we need you; now more than ever we need our arts graduates; now more than ever, we need those who--as I mentioned in my December 12 remarks--can see those shades of complexity, can address all sides of nuanced problems, and are comfortable with the ambiguity with which solving a problem like the 2020 pandemic will require us to come to terms.

Your education has prepared you for a lifetime of creativity, problem solving, tenacity, and continuous intellectual development. Don't let the difficulties that we face right now cloud your perspective on the opportunity that you have to make an impact and change the world. I know the difficulties seem insurmountable sometimes. They are not. You can solve any problem and improve any situation; your education has prepared you to do so. Make the decision that you will, and go do it.

I thank each and every one of you for your contributions to the McGovern College of the Arts and to the University of Houston. On a personal note, I thank you for sharing and weathering these last couple of months together with me. I'll miss you all once you leave our campus. Don't be strangers; drop me a line, or come say hi next time you're nearby.

Congratulations again and best wishes.

Andrew Davis

Dean