Recreating the Steps to Malignancy Leads to Faster Drug Discovery

Using cloning technology to aid in the understanding of the evolution of cancers, Frank McKeon, professor of biology and biochemistry and director of the Somatic Stem Cell Center at the University of Houston, is leading a team to recreate the sequence leading to esophageal cancer. The goal is to identify potential targets for therapies before the disease becomes fatal. Esophageal cancer will kill an estimated 16,000 Americans in 2019, according to the National Cancer Institute.

“Our cloning provides unprecedented resolution to genomic changes accompanying this evolution and provides multiple advantages for drug discovery,” said McKeon, whose work is funded by a $2.2 million grant from the National Cancer Institute. McKeon’s research group includes Wa Xian, University of Texas McGovern Medical School in Houston, Jaffer Ajani, M.D., The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, and Peter Davies, Texas A&M University.

McKeon said his team can develop effective drugs in a fraction of the time it might take Big Pharma.

“We have something that most drug discovery labs do not – the clones commonly hit in chemotherapy – liver and gastrointestinal stem cells – to test at the same time and show they’re not effected. We’re not wasting our time on drugs that are going to lead to toxic surprises downstream. We can be very sure of the ones we focus on,” said McKeon, who is on the faculty of the UH College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics .

The average life expectancy of patients diagnosed with esophageal adenocarcinoma is just one year and considerable efforts are devoted to defining its development in a predictable progression called the “Correa sequence.” It’s a 20-year evolution that starts with a precancerous lesion known as “Barrett’s esophagus,” then progresses to dysplasia before becoming a malignant esophageal adenocarcinoma.

“We are reconstructing a tumor that took 20 years to develop by applying stem cell cloning we originally developed for the human gastrointestinal tract to reconstruct the Correa sequence in patients with early esophageal adenocarcinoma,” McKeon said.

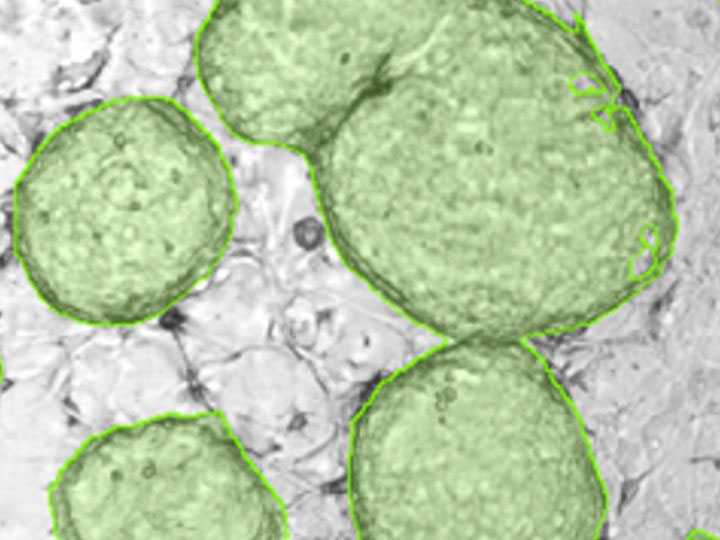

From patient-matched endoscopic biopsies of Barrett’s, dysplasia, and esophageal adenocarcinoma, McKeon’s team has cloned stem cells representing each of these lesions and has used molecular genetics to reconstruct the Correa sequence with clonal precision not possible from the sequencing of biopsies alone.

“The cloned stem cells of Barrett’s, dysplasia, and adenocarcinoma have enabled powerful forms of drug screens as well as in vivo models of the Correa sequence to validate lead combinations that specifically and simultaneously target the entire Correa sequence lineage,” said McKeon, who believes patients deserve better.

“Nobody can really manage esophageal cancer; it is most often linked with bad outcomes. We need to get at it at these earlier stages to see if we can address it in a pre-emptive way,” said McKeon.

- Laurie Fickman, University Media Relations