Tom Teets and Fan Wu Find Student Motivation and Self-Regulation Decreased

“Like everybody else, we were stuck at home, and instead of watching Netflix, we did a chemistry education study.”

Tom Teets and Fan Wu spent much of their time in the early days of the pandemic conducting a study to examine student motivation and engagement in a chemistry class.

Teets, associate professor of chemistry at the University of Houston, has taught general chemistry for seven years, a course that can be a major hurdle to students trying to move forward with their degree plan. Even before the pandemic, he and Fan Wu wanted to survey students regarding their engagement and motivation in the introductory class. Wu is assessment and evaluation analyst for the Cougar Initiative to Engage office within UH’s Office of the Provost.

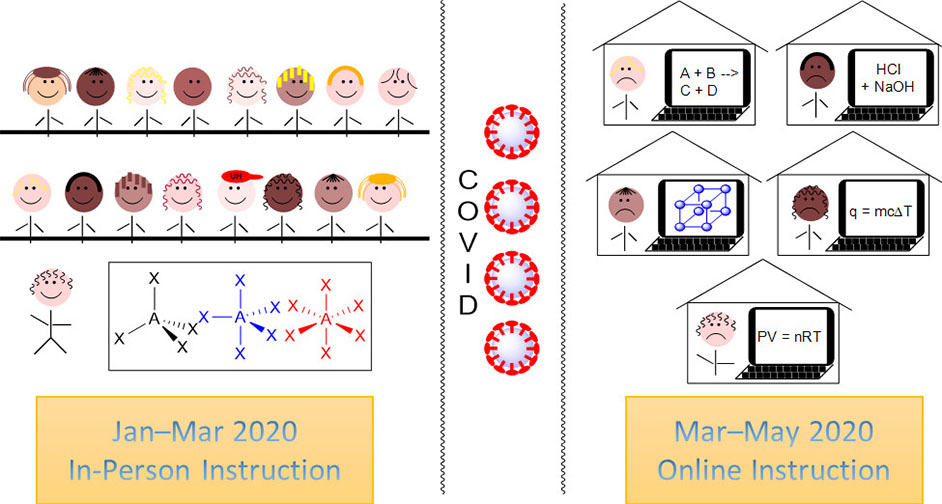

When COVID-19 broke out in the U.S., a unique opportunity presented itself to begin the study during a major globally historical event.

Teets and Wu carried out the study in Teets’ spring 2020 “Fundamentals of Chemistry I” course. Together they published their findings in a paper titled “Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Student Engagement in a General Chemistry Course,” in the Journal of Chemical Education in November 2021.

“We were interested in seeing how that sudden change and the events of the pandemic would change student engagement,” said Teets.

He and Wu defined engagement as a concept that encompasses effort in the course, the amount of activity students invest in their studying, attitudes about the course and the social aspects of learning collaboratively. Their study measured four factors of student engagement: skills, emotion, participation and performance.

They asked all 516 students enrolled in the class if they wanted to be surveyed for a 0.5% bonus credit toward their final grade. 431 students completed the survey.

Students responded to 19 questions designed to assess how their activity in the course changed after the switch to remote instruction. Some of those questions asked whether students made sure to study on a regular basis, whether they stayed up to date on the readings, or if they sought help from the instructor. Students responded using a five-point Likert scale format, ranging from 1 (significantly decreased) to 5 (significantly increased). This was the quantitative part of the study.

The qualitative portion was based on student responses to an additional, optional essay question, which asked: “After the coronavirus outbreak, how has online instruction changed your learning in the general chemistry course?” 406 students answered this final question.

Findings Point to Decreased Engagement

From the quantitative results, they found students’ engagement decreased after the coronavirus outbreak.

“We compared different groups, and we found underrepresented minorities’ engagement decreased more than non-underrepresented groups in three of the four components,” Wu said. “That was a major finding.”

Almost half of respondents came from underrepresented minority groups. Sixty-three percent were female. Additionally, a third of respondents were first-generation college students.

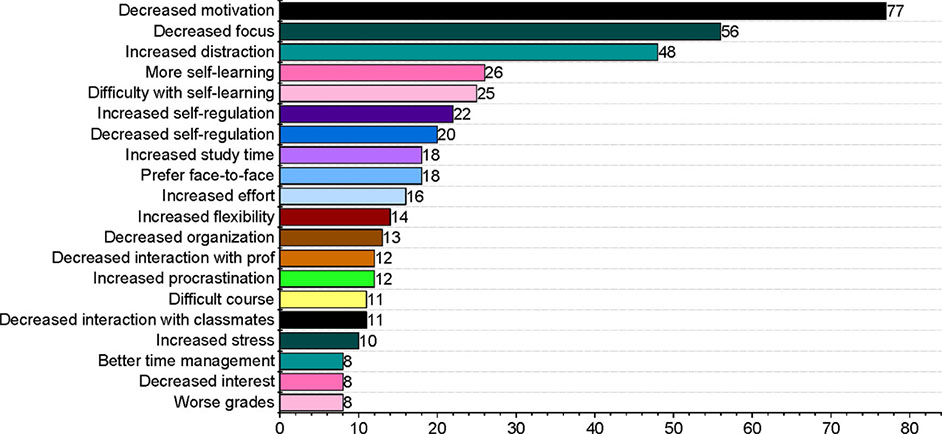

From the essay responses, motivation and self-regulation emerged as the two clearest themes. Seventy-nine responses mentioned motivation, 77 of them reported a decrease in motivation. Teets and Wu write, “many of these stated their coursework became less important or reported a lack of interest in chemistry against the backdrop of the global pandemic.”

One student wrote, “I find it hard to stay current or consistent with the material because I now work extra hours to fill in for those that were laid off at my job. I find it hard to find the time or motivation to study. Showing up to class and being forced to pay attention is a more structured and normal approach to my education, so I find it extremely difficult to stay disciplined and on task during the COVID-19 pandemic.”

The next most-prevalent themes of the essays were decreased focus and increased distraction. Students wrote that being on campus in a classroom environment was conducive to their studies, while the presence of family members at home made it challenging to self-regulate their academic schedule and learning habits.

Another student wrote in part, “online instruction has made it much more difficult for me to focus during the lectures. Because my entire family is home, my house can be noisy and chaotic, and it can be difficult to find a space that is quiet that allows me to have full focus.”

‘Beyond Instructor’s Control’

Teets and Wu hope their study is insightful to other chemistry professors and helps them adjust their instructional approaches for future semesters.

“We might get to a post-pandemic state where online or hybrid classes can be a portion of students’ courses,” Wu said. “I think it will be nice to provide some mentoring or counseling to students, not only regarding their mental health, but also on how to adjust to the online classroom, how to effectively study in an online environment, and how to connect with your professors.”

However, Teets admits there is only so much an instructor can do during a global pandemic to effectively educate students.

“I think what we learned is a lot of it is beyond the instructor’s control,” he said. “There are some instructional techniques we can use to make sure students still feel connected to the course, but how do we reign in their focus when there are so many other things going on that they have to divert their attention to or that encompass their thoughts.”

For example, one student shared an honest and sobering picture of the reality of the pandemic.

The student wrote, “I do not believe online instruction is affecting me the most. I believe it is the fact that we are expected to still be a fully functioning student during a global pandemic. It’s hard to focus when I witnessed my mother having breakdowns due to losing her brother, someone whom she loved very much, to COVID-19, along with seeing both my parents get laid off. This leads me to stress about other things instead of school, which leads it to not be just the fault of online schooling.”

- Rebeca Trejo, College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics