Geologic Field Methods Trip to Big Bend 2024

Day-by-Day Reflection on the Annual Spring Break Field Geology Excursion

By Lucille Baker-Stahl, Teaching Assistant

Context

Geologic Field Methods (Geol 3340) is a core course in the UH Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences (EAS). It is a required course for the Geology B.S., Geophysics B.S., Environmental Geoscience track of the Environmental Science B.S. and the Earth Science B.A. As a TA, I see the class as a fantastic opportunity to learn from the ground up, how to take measurements and make interpretations in the field. It involves six outdoor labs on UH main campus to practice techniques before applying them in two field trips.

Our first trip was a weekend visit to Central Texas’s Pedernales Falls and Enchanted Rock State Parks in the middle of February. Students practiced geology during the day and camped at Pace Bend Park for the night. This provided a chance to try out camping and fieldwork for a short duration. Many were doing both for the first time, and it provided a fantastic low-stakes opportunity to practice and identify what they needed to take care of themselves without some of the city conveniences they are used to. It was also a community experience through long van rides together, shared experiences and community living.

Big Bend - March 9–15, 2024

Every spring break, Field Methods heads to Big Bend National Park to experience an extended field geology excursion. The trip typically lasts seven days with five full days in the park and one day for driving each way. We camped at Stillwell Ranch for the six nights of the trip. It was a lovely little campground and RV park only a 10-minute drive away from the entrance to the park. It had bathrooms, showers and a small store a five-minute walk away from our tent sites. The store even had limited Wi-Fi for staying in touch with friends and family back home!

Day 1, March 9, 2024

Driving, driving, driving! A long day with an early morning meetup in lot 12A on UH campus before loading up vans and making the long drive. Gas/food/bathroom stops ~every 2 hours with, of course, a mandatory Buc-ee’s stop in Luling. Another guaranteed stop at the Lowe’s grocery store in Fort Stockton for any last-minute groceries before caravaning the last segment into camp.

The day ended as we arrived just as the sun was setting, still giving everyone enough time to set up tents and cook dinner before preparing for an early morning field day the next day.

Day 2, March 10, 2024

The first field day! We woke up early to cook breakfast and pack day bags before the field. We also had a short lecture at the box truck before leaving. Highlights include:

After learning about where we were headed, we left to drive to our field site in the Northwestern corner of the park. This place would become very familiar to the students soon enough, but the first day was to get a lay of the land and understand the stratigraphy of the mapping area.

We started by using Jacob’s Staffs to measure the thickness of the different geologic units in the area. By tilting the staff at the same angle as the bed is tilted, we can estimate thickness accurately to inform our stratigraphy of the region.

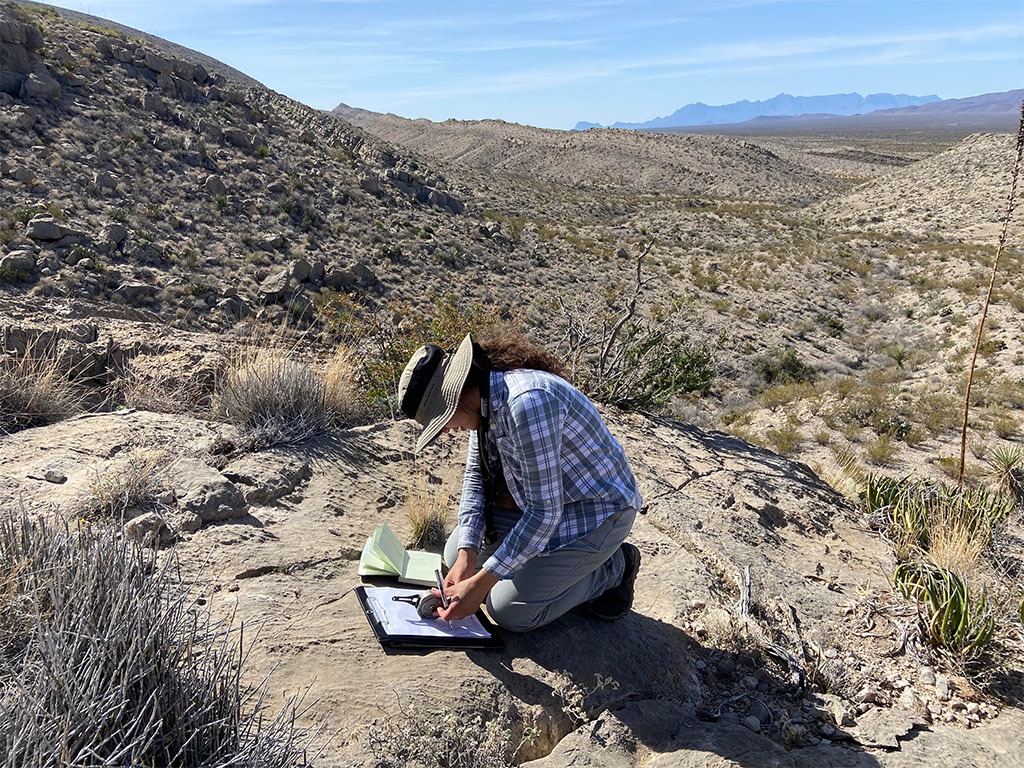

In addition to measuring the thickness of the regional stratigraphy, students also took the time to make descriptions of the rocks in the area. This included identifying the rock type, the texture, grain size, color, and any additional features present.

Day 3, March 11, 2024

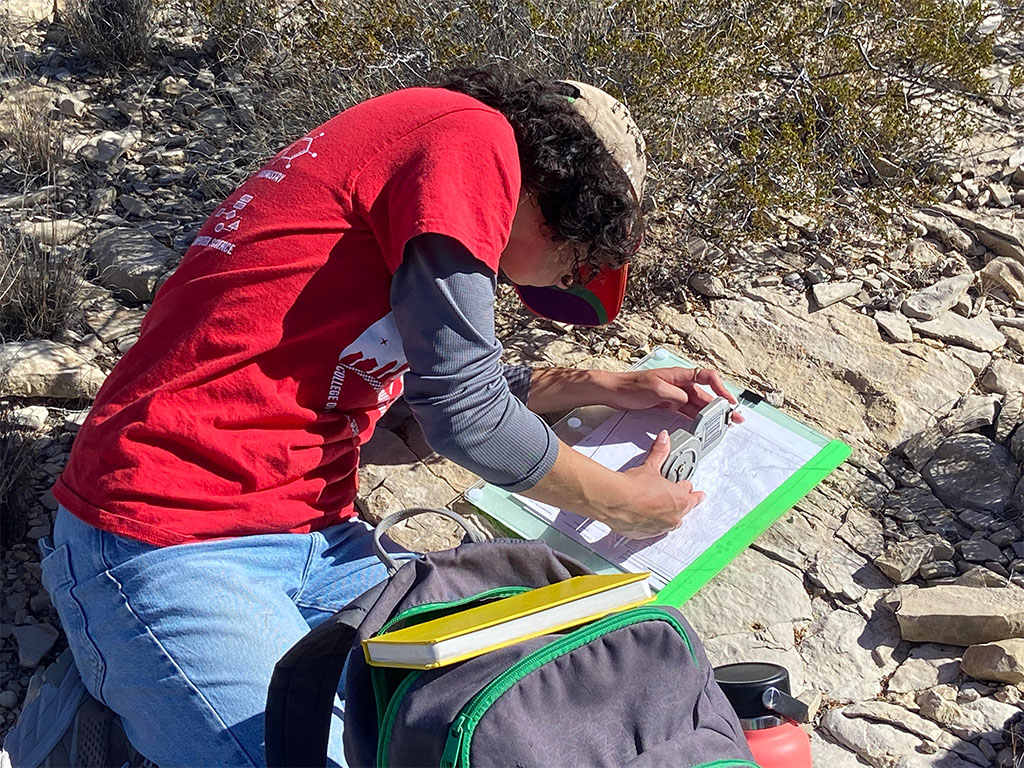

On our second field day, mapping began in earnest. Students were expected to make use of their knowledge of the stratigraphy and rocks present in the area to figure out their distribution. One of the most useful tools for this, aside from understanding the rocks being mapped, is a Brunton compass. It can measure bearing and inclination to determine the spatial orientation of a bed. With this, students know where to look to follow that bed in addition to where to go to find contacts with new units. It can also help them find where they are on a map by taking a bearing to reference points.

Students split into mapping groups of 3–4 for the day to cover more ground. This was their first chance to choose where to explore within the mapping area. They spent the whole day mapping, from around 9 am until meeting up at the vans at 5 pm to head back to the campground. It was a chance to feel more confident in their own interpretation skills as they were left to their own devices. However, a teaching assistant or professor was never very far.

After a long day, we returned to camp. Many relaxed and cooked dinner before heading off to bed. However, some took the evening as a chance to connect and have fun resulting in a game of Pictionary after borrowing the whiteboard used for field lectures.

Day 4, March 12, 2024

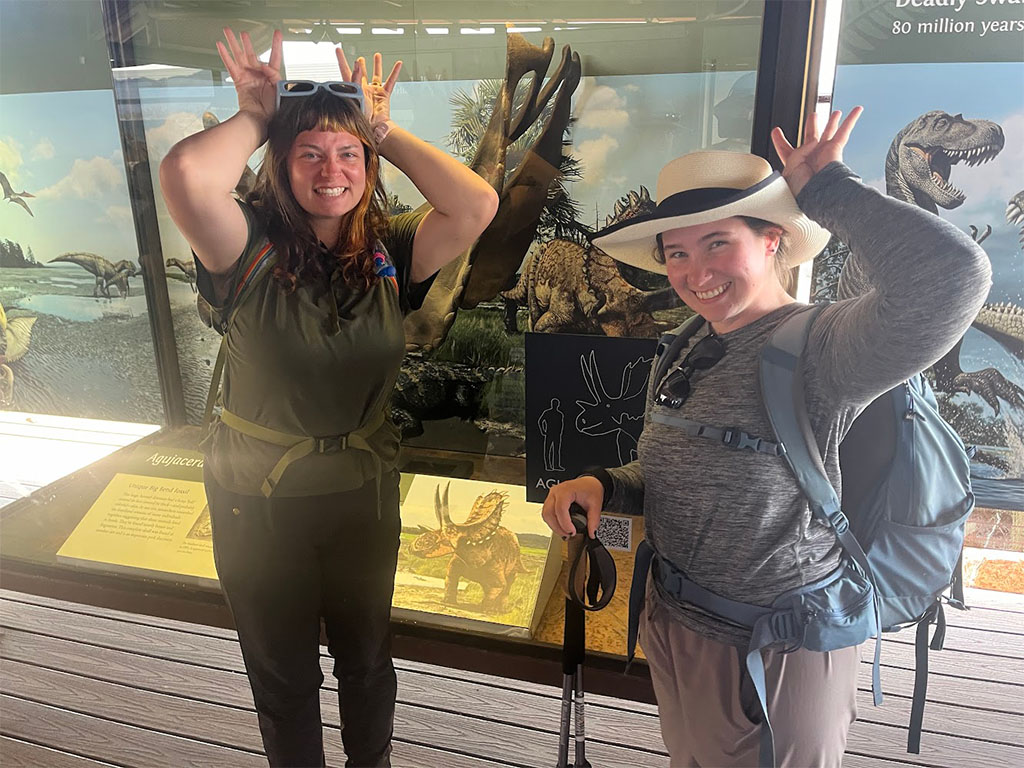

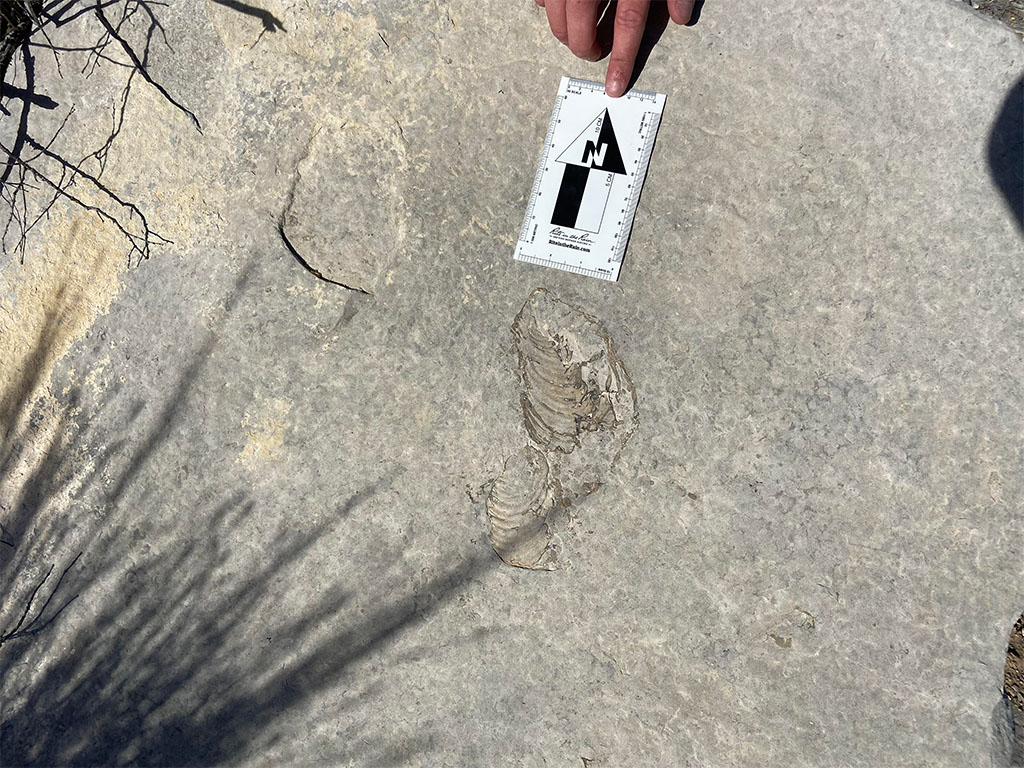

Today was only half a workday in the morning before transitioning into geotourism! We started off by visiting the park’s Fossil Discovery exhibit. The site had been used to display fossils in the park for over 50 years(!) and today contains not only a host of specimens found in the park but also many displays and explanations showing how the fossils are used to piece together the geologic history of the site.

After visiting the Fossil Discovery exhibit, we took a ride to a beautiful exposure of terrestrial sediment deposits which formed after the region was no longer covered by ocean.

After a shorter day than the first, we returned to camp to rest and work on the mapping project. It also became an occasion to take a fossil hunting expedition outside the National Park in a place where students could collect and bring home their own specimens!

Day 5, March 13, 2024

The last day of the mapping project. It was a long field day from 9–5 but a great chance to get final measurements collected and fill in spots on the map they hadn’t reached yet.

After a long day in the field with the discovery of not only one, but two, faults in the back of the map area, we returned to camp. Now it was time to spend the evening working on their maps.

Day 6, March 14, 2024

The day started off with a field final. Students were brought to a different area just down the road from the mapping project and given a much smaller area with the same rocks they were familiar with to map.

After the field final, we still had half a day of fun to explore the park! This resulted in a group trip to hike Boquillas Canyon followed by a swim in the Rio Grande River.

Back at camp, we were greeted by a beautiful sunset providing light to pack.

Day 7, March 15, 2024

We got up early on the last day to take down tents and pack all our things into the box truck for our return to Houston.

Some Reflections on Big Bend

As a teaching assistant, it is always wonderful to take students out to the field. It can often be stressful as an instructor, needing to manage not only student learning but making sure that they are taking care of themselves 24 hours a day in environments they’ve never experienced before. Nevertheless, I never seem to stop loving teaching through field studies. The visceral nature of discovering something for yourself, perhaps with the guidance of the instructor, will always remain for me more meaningful than what can be learned in the classroom. There is a difference between being given a lecture or doing a worksheet on a topic and taking the time to make use of all the concepts you have learned and using them to piece together a story of an area’s geologic history. That’s what a map is to me, a story millions of years old that has played out though changing climates and environments, modulated by tectonics going on thousands of miles away, all shaped by ancient organisms who ceased to exist except as fossils long before humans ever walked on the land. That is something that I don’t think can be fully understood without taking the time to put together one’s own story of the landscape, one’s own map. I hope it means as much to the students who came on this trip as it did to me, the act of taking the time and learning from mapping in the field. Regardless, it is certainly an experience that none of us will ever forget. An experience that connected us all far more than is possible in a classroom.

A Note on Accessibility

As intense an experience as taking a trip like this can be, both mentally and physically, it is an experience that can be undertaken by anyone. All components of the course that are connected to a student’s grade can and have been adapted to meet individuals’ needs. Having had the pleasure of working with students who could not necessarily hike out to the farthest edges the mapping area, or internalize geology concepts the same way I have, I still see this trip as something that can be meaningful and rewarding for everyone.

Working with Dr. Robinson, the professor who taught the course, he is more than willing to meet students where they are and not demand more of them than they can give. It may require hard conversations, taking the time to understand one’s own limits and sharing them with another to maximize what the experience can be. No one will ever have the same experience going on such a trip. Nevertheless, the experience still has meaning and growth associated with it, whatever it may be. Whether it be an increase in knowledge of geology, or self-discovery, or simply a different perspective on the world we live in, there is room for everyone to learn in the field, including a teaching assistant like me.

On the flip side, field geology is not, and never will be, the only geology that exists. I consider myself largely a field geologist. And yet, there is so much more that can be done outside the field by incredibly talented and brilliant individuals, who will likely go on to make much greater contributions to geology than someone like me who has discovered that I need to be able to go out to the field in order to further my science.

As a part of UH’s curriculum, I value this class for going out to the field to give students a taste of my perspective on geology. I encourage all who can, to partake in such an experience. I also encourage you to see past the outdated notion that the quintessential nature of geology is field science. I look forward to seeing where the students who went on this trip will go and hope they catch on that there is no need to pigeonhole yourself into an idea of what a geologist is.

We try to understand the earth and the planets in whichever way we choose, through whatever methods we choose. A concept at the heart of geology is uniformitarianism, that the way the Earth behaves today is the way in which it has behaved in the past and vice versa. I do not see the same concept as true in the study of geology. The past does not equate to the present or to the future. We simply teach students what geologists do and have done historically.

It is up to them, the students of today who we take to Big Bend, to learn and grow from what we teach in order to rewrite their future as geologists. Not as the same geologists who are teaching them, but the geologists they are choosing to become.