Svalbard 2024: A Journey to The End of The World

By Shannon Penelope Dixon, Planetary Geologist, Geology Major Graduating December 2024

Above the Arctic Circle, in the Arctic Ocean, lies the remote archipelago of Svalbard. Known for its stark beauty and extreme climate, it sits at the edge of the world – just 800 miles from the North Pole. Here, the sun doesn’t set for months during the summer, casting a perpetual glow over the landscape. The midnight sun bathes the glaciers, mountains, and fjords in a surreal light. It’s a place where time seems to stretch, lines between day and night blur, and the sheer expanse of wilderness stretches on and on.

Amidst this wilderness lies the small city of Longyearbyen, the northernmost settlement on the planet. Despite its isolation, Longyearbyen is a vibrant community, home to a diverse mix of residents from all over the world. This town, with its colorful houses dotting the valley, is a testament to human resilience and adaptability. The residents of Longyearbyen have the rare, shared experience of living at the edge of civilization.

Geologic Tapestry of Svalbard

Svalbard’s landscape is a geological record of Earth’s ancient history. The rocks here date back over 400 million years, bearing witness to the formation and breakup of supercontinents, the rise and fall of ancient seas, and the movement of glaciers. Glaciers still dominate the terrain, carving deep valleys and fjords. Just beneath the surface lies permafrost, a frozen remnant of colder times, silently shaping the land.

Permafrost: Silent Guardian of the Arctic

What is permafrost?

To be brief, permafrost is more than just frozen ground; it’s a critical part of the Arctic ecosystem. In Svalbard, it stabilizes the ground, influences groundwater flow, and acts as a vast storage system for carbon, methane, and ancient organic matter. It also serves as a natural archive, preserving evidence of past climates and ecosystems.

Why should we care?

As global temperatures rise, permafrost thaws, releasing stored carbon and methane, which accelerates climate change. This isn’t just an Arctic issue—it has global consequences. Understanding permafrost is essential for predicting future climate scenarios and finding ways to mitigate climate change. In Svalbard, where the effects of warming are already visible, studying permafrost is a race against time to protect one of the planet’s most vulnerable climate regulators.

My journey to Svalbard was driven by a desire to immerse myself in this extreme environment, to study permafrost and its dynamic implications for Earth and beyond. As a planetary geologist, I sought to hone my skills in the Arctic, where the harsh conditions can be used as an analog for studying other planets. This journey was about more than research for me, arriving in Svalbard felt so special.

WEEK 1

After 21 hours of travel from Houston to Frankfurt, Oslo, and finally Longyearbyen, I arrived in Svalbard feeling both exhausted and exhilarated. The moment we broke through the clouds and saw the snow-covered peaks and glaciers below, there was a small gasp from everyone on the plane; we were entranced by the beauty of the landscape. As I stepped off the plane into the crisp Arctic air, the reality of where I was began to sink in. I was welcomed to the tiny Longyearbyen airport by a polar bear guarding the luggage carousel. After my bus ride to the student housing, I spent the weekend settling in. I organized and decorated my apartment, visited the local grocery and shops, explored the outer edges city, and did my best to catch up on sleep. I spent a lot of time journaling and reflecting on the journey ahead, mentally preparing for what was awaiting.

Survival and Safety Training Begins

The first day of the course was all about safety – something that’s taken very seriously in Svalbard – especially at University Centre in Svalbard (UNIS). We started with survival training by spending time in the logistics center going over equipment and gearing up in survival suits to take our first cold plunge. We headed down to the sea and jumped off the dock; nothing could have prepared me for the shock that came from jumping into the freezing ocean! We learned how to arrange ourselves to swim as a unit and how to care for each other in the water, vital skills for any fieldwork in a remote and unforgiving environment, especially since we would be making many trips by boat.

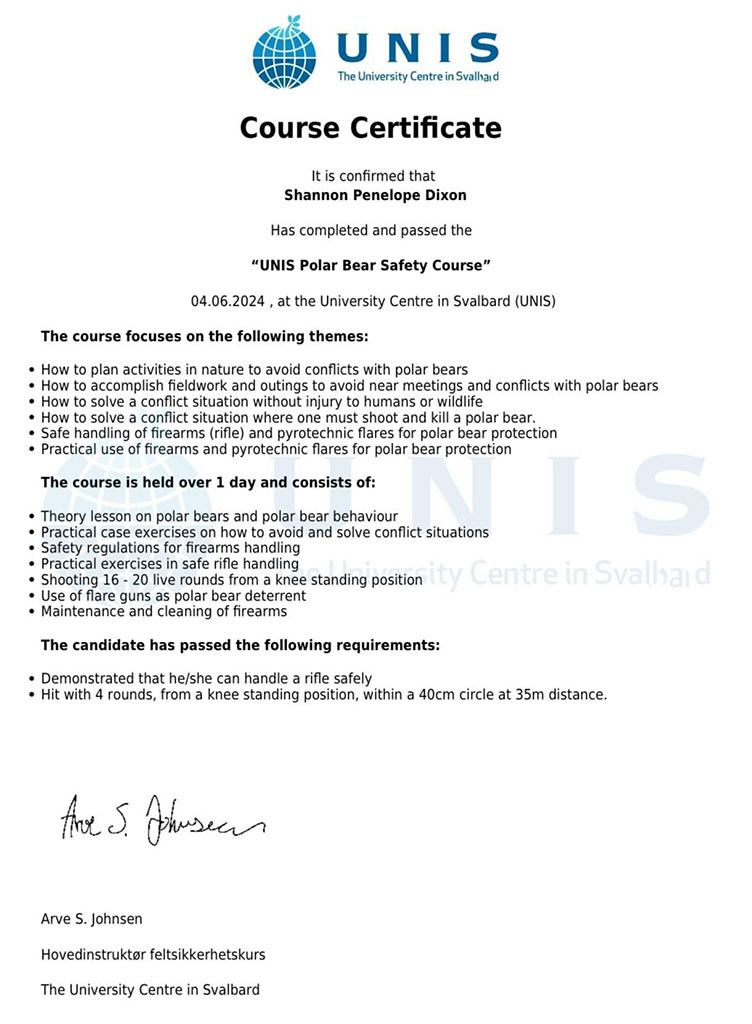

Polar Bear Safety and Shooting Practice

On Tuesday, we moved on to polar bear safety training, another aspect of living and working in Svalbard. Spending several hours learning about past attacks and deaths on the archipelago was enough to make my blood pressure spike. The day was spent at the rifle range outside of town, learning how to shoot and handle firearms responsibly, with a huge emphasis on how to avoid/diffuse a situation with the use of flares and only using firearms as a last resort. We practiced for hours, preparing for the possibility of encountering a polar bear in the field. Later, we put our skills to the test with a guided exercise that simulated a polar bear encounter. This training not only taught us how to responsibly defend ourselves, but also emphasized the importance of planning, communicating, and working together as a team in the field. Every decision we made in the field could mean the difference between life and death.

Wednesday brought a welcome change of pace from the intensity of the previous days. We spent it hiking through Longyearbyen, exploring the town’s rich history. One of the most memorable stops was the graveyard, where we learned about the devastating impacts of the Spanish influenza, which reached even this remote island, and the tragic 2016 landslide that claimed several lives. Later that evening, I met Nastya at the Kulturhuset to see a jazz concert of a duo from Tokyo, Music for Isolation. Their sound was hauntingly beautiful; it created a serene, almost surreal atmosphere inside the warm, cozy café listening to live music as snow lightly fell outside the window. It gave me joy seeing art and culture thrive here at the edge of the world.

Thursday and Friday

Thursday marked the start of our academic work. We spent the day in the lab, analyzing temperature data to determine the active layer depth of the permafrost by generating trumpet curve graphs. It was engaging, and I was eager to learn how to analyze permafrost more effectively, pinpoint the active layer depth, and interpret trumpet curves. This was the first real taste of the scientific work I had come to Svalbard for.

On Friday, we continued our lab work until lunch. In the afternoon, the weather was so beautiful that Marjo gave us the rest of the day to explore. Sophia and I took the opportunity to wander through the city, enjoying cappuccinos in the sun. Later, we met up with some of the others and spent the evening together, making the most of the endless daylight. I learned a few words in German and Norwegian. Since the program is in English, it felt really meaningful to connect with others in their native languages.

Saturday and Sunday

On Saturday, we visited the local flea market, where I found a pair of hard-shells, windproof trousers, perfect for the upcoming days in the field. Later, I took a walk to the beach, enjoying the sunshine and listening to music.

Sunday started with a yoga session I led in my apartment with Nastya and Sophia. Afterward, we headed to the Svalbard Museum, where we explored displays of traditional clothing, instruments, traps, cabins, and historical photos of Svalbard and Longyearbyen, dating back to its discovery by Dutch explorer Willem Barentsz in 1596. The museum also showcased taxidermy animals native to the Arctic ecosystem, alongside exhibits about the region’s rich history and the coal miners who made life here possible.

After the museum, we visited the bird-watching house by the sea and eventually made our way down to a mouth bar, where I found a perfectly heart-shaped rock.

Week 2

Monday

We started the week with an intensive session on geotechnical engineering in Svalbard, led by Arne, an engineer responsible for many critical projects on the island, including helping design the Global Seed Vault. The day was all about understanding the unique challenges that come with building infrastructure in permafrost environments. Arne explained how essential it is to consider permafrost in construction. For example, many buildings in Longyearbyen are built on piles to avoid building subsidence resulting from the changing thickness of the active layer due to seasonal and general thawing, and to avoid the formation of taliks – thawed patches in the permafrost that destabilize the ground. One of the major issues we discussed was how groundwater flows over the permafrost table, leading to significant icing problems. In summer, the water melts, and then in winter, it re-freezes and expands, causing ground subsidence and structural movement. The soil type plays a crucial role here; coarse materials like sand and gravel are preferable for building because they hold less water, while fine marine materials like silt and clay can trap water, causing major icing problems.

A prime example of these challenges is the student housing where I’m staying. Despite warnings from geotechnical engineers, like Arne, the city built a five-story building that is allegedly too tall and too hot for the underlying soil. This has led to significant problems, including cryostatic pressures causing groundwater to burst through cracks in the permafrost, leading to significant icing beneath the structure. Last year, the emergency door couldn’t be opened because the platform it was on had been raised by the ice.

We also learned about and visited the seed vault, which, despite its reputation as one of the most secure facilities in the world, had to undergo significant modifications after its construction. In 2016, engineers had to install an artificial cooling system beneath the vault because of unexpected groundwater flow that was causing permafrost to thaw. Now, the entire side of the mountain where the vault is located is kept at -20°C, with the hallway maintained at -10°C to ensure the long-term viability of the seeds. This was a stark reminder of the importance of thorough risk assessment and the sometimes overlooked, yet critical, role of geotechnical engineering.

Tuesday: Field Trip to Colesbukta

Tuesday was our first full day in the field and far from town. We met early at UNIS to gear up in survival suits and gum boots before heading to the harbor. From there, we took a Polarcirkel speed boat and traveled 13 kilometers south to Colesbukta (Coles Bay), an abandoned Soviet settlement that was inhabited from 1912 to 1965.

As we approached the coastline, we scanned the shore for polar bears. Once the boats got closer, two people from each boat disembarked with rifles and flare guns to inspect the area, including the abandoned buildings, ensuring no polar bears were hidden inside. With the area secured, the rest of us unloaded into the water. We worked together to unload our gear and carry it to shore. After getting out of our survival suits and into our field clothes, we left the suits packed together on the beach for when we returned later in the day.

We spent the day exploring the remnants of Coles Bay. Many of the buildings had completely collapsed, giving us a firsthand view of the long-term effects of permafrost thaw and the consequences of neglected infrastructure. The political tensions between Norwegian and Russian settlements in Svalbard were also a point of discussion, providing a geopolitical layer to our technical studies.

As we walked up and down the coast, we inspected the structures and surface soil conditions. The material here seemed to fare better than in Longyearbyen, likely due to the coarser soil, though we couldn’t confirm whether there was finer marine material beneath without a soil inspection. We explored the old coal mine, which had completely collapsed, the remains of the cable car railway, rickety wooden bridges, a small cemetery, an old football field, and a rock core repository.

Over the course of our 7-hour hike around the bay, we spotted countless reindeer, a pack of walruses, an arctic fox, and even a lone seal. The weather was cold, and the seas were rough on our return trip, but the experience was worth it.

That evening, I went to the church on the hill for the last performance of the jazz duo I’d seen earlier in the week. They had composed two new songs about Svalbard since I last saw them, and the performance was enchanting. The setting of the church added to the atmosphere and acoustics, making it even more special. After the show, I spoke with the musicians, and they remembered me from before, which was touching. We shared a warm hug, and they let me photograph of them in front of the beautiful church mural.

I was joined by Hannah, Kathi, and Sophia, and we stayed after the performance to enjoy free Norwegian waffles and coffee. (Hannah insisted I try them with fresh cream and berries; she was right, they were amazing). I ended the evening with Sophia; we shared a laugh and a cigarette while reminiscing on how many beautiful days we’d already shared together.

Wednesday

The day began slowly, with most of us still recovering from the physical demands of the previous day in the field. But things quickly brightened when Nastya took the podium to present on the sociological aspects of permafrost. As a social scientist with a deep interest in Arctic communities, she offered a unique perspective on the intersection of culture and climate science.

Nastya’s lecture focused on how different societies view and interact with permafrost, with a particular emphasis on the cultural differences between Russian and Norwegian settlements in Svalbard. Originally from Belarus and having spent several months in Barentsburg—a coal mining town predominantly made up of Russians and Ukrainians—before coming to Longyearbyen, Nastya had firsthand experience of these contrasting communities. She discussed the historical context of permafrost, how its management has evolved over time, and how various communities relate to it, both practically and culturally.

Her presentation was deeply moving, leaving me with a more nuanced understanding of permafrost and climate science. It was a reminder that our work here isn’t just about the science—it’s about the people who live in these extreme environments and how intertwined their lives are with the land.

Thursday

Today was my 23rd trip around the sun! It was a day full of learning and celebration. We spent the morning at UNIS diving into lectures on ground ice and geophysical methods for studying permafrost. The sessions were detailed and provided valuable insights into how we can assess permafrost conditions using non-invasive techniques like Electrical Resistivity Tomography (ERT).

In the afternoon, my friends surprised me with a small birthday celebration. Then, we went to the new Thai restaurant in the Lompensenteret where we enjoyed a nice meal. The highlight of my day was the cinnamon roll cake Sophia baked for me. I was very touched by the fact she took time to run to the grocery and bake during our lunch break, just to surprise me. Getting to share the celebrations with my new friends helped me feel more at home in the Arctic.

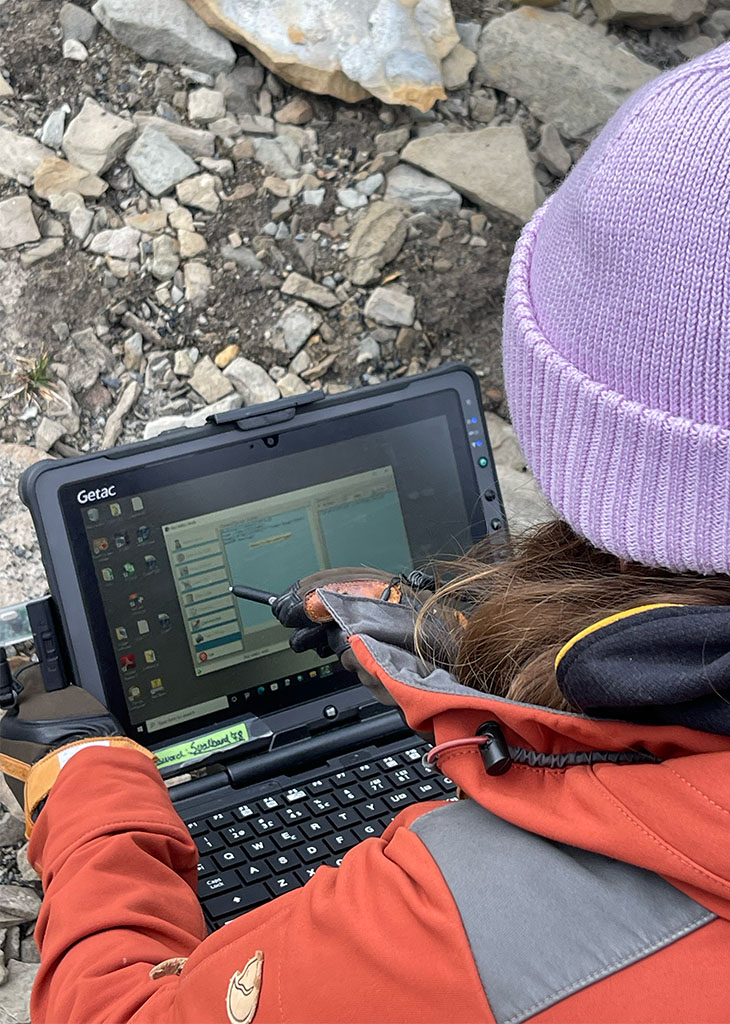

Friday: ERT Fieldwork at the Landfill

Friday was another intense day in the field. We headed out to the local landfill at 8 a.m. to set up an Electrical Resistivity Tomography (ERT) line, with the goal of gathering geophysical data on the permafrost below. The morning was spent hauling heavy equipment and carefully running cables down a hill, being mindful not to drag them and disturb the delicate tundra.

The cold conditions made the physically demanding work even tougher, but it was satisfying to finally collect the data we needed. We also conducted thaw depth measurements to assess the thickness of the active layer above the permafrost. This involved throwing our full body weight onto small probes to penetrate the ground, which looked a bit ridiculous but was essential for measuring the active layer depth. This data was crucial in determining the presence (or lack) of permafrost beneath the landfill, and our findings confirmed there was none directly beneath the landfill.

Saturday: Hiking to Bjorndalen

On Saturday, we hiked to Bjorndalen to spend the night at the student cabin. The hike itself was all but challenging until when we had to cross the river, which left my shoes soaked. But the cabin was a cozy reward at the end of the journey.

We spent the afternoon gathering wood for a bonfire and cooking sausages and stick bread over the fire (Hannah makes the best stick bread). For dinner we worked together to make a large pot of curry and played card games. Later, we danced outside in the midnight sun—a moment I had been looking forward to since before arriving in Svalbard. It was a simple, joyful celebration of being here, in this extraordinary place, surrounded by good friends.

Sunday: Arctic Ocean Plunge

Sunday took us from the peaceful isolation of the student cabin back to the more familiar routine in Longyearbyen. We started the morning with some yoga; I led us in a flow after cleaning the cabin. Afterwards, a few of us braved the Arctic Ocean for a quick, freezing dip. The water was shockingly cold, but the experience was exhilarating. Afterward, we sat on the beach in our wet clothes, taking in the moment before beginning the hike back to town.

Once we returned, Sophia and I sat at a picnic table surrounded by all our gear, smoking a cigarette. A group of tourists passed by, snapping photos of us on their way back to their cruise ship. It felt funny and a bit surreal, being treated like part of the spectacle while we were just minding our business. After that, it was back to the usual—grocery shopping, laundry—before collapsing into bed, completely wiped out.

Week 3

Monday: Data Analysis and Prepping for Drilling

We spent the day analyzing and interpreting the ERT measurement data we collected on Friday, using a program called IPSY. It was satisfying to see the data come together and start making sense of the permafrost layers we had been studying. Later, we headed to the logistics warehouse to set up the equipment we’d need for the drilling in Adventdalen the next day.

The highlight of my day, though, was receiving my On To The Future Scholarship letter from the Geological Society of America Connects Conference. I couldn’t hold back the happy tears!

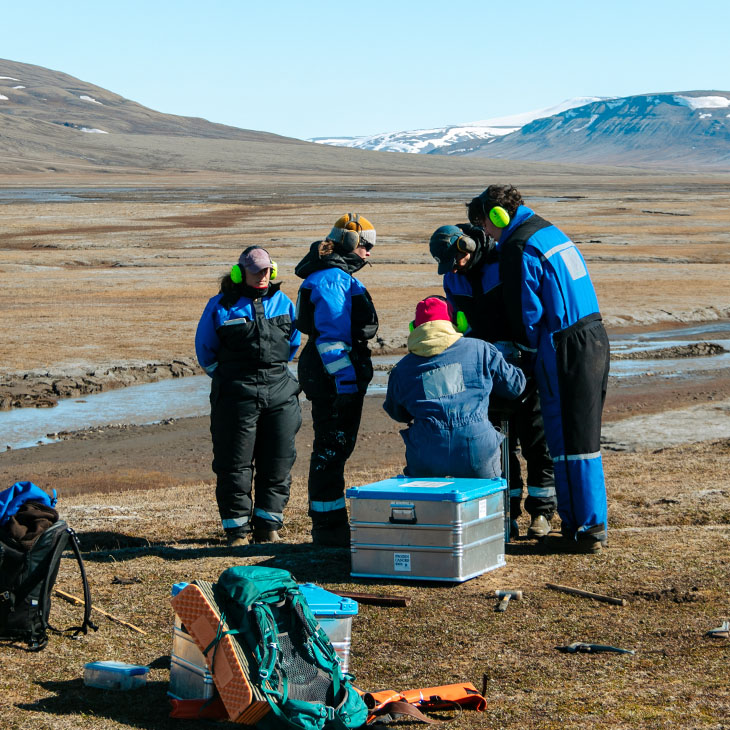

Tuesday: Drilling Day!

Today was incredible—the fieldwork day in Adventdalen I had eagerly anticipated. We hiked out into the tundra carrying 12 large boxes of heavy drilling equipment and spent about six hours in the field drilling permafrost cores. The best part? We broke the UNIS depth record for student drilling, reaching 285 cm (the previous record was 240 cm)!

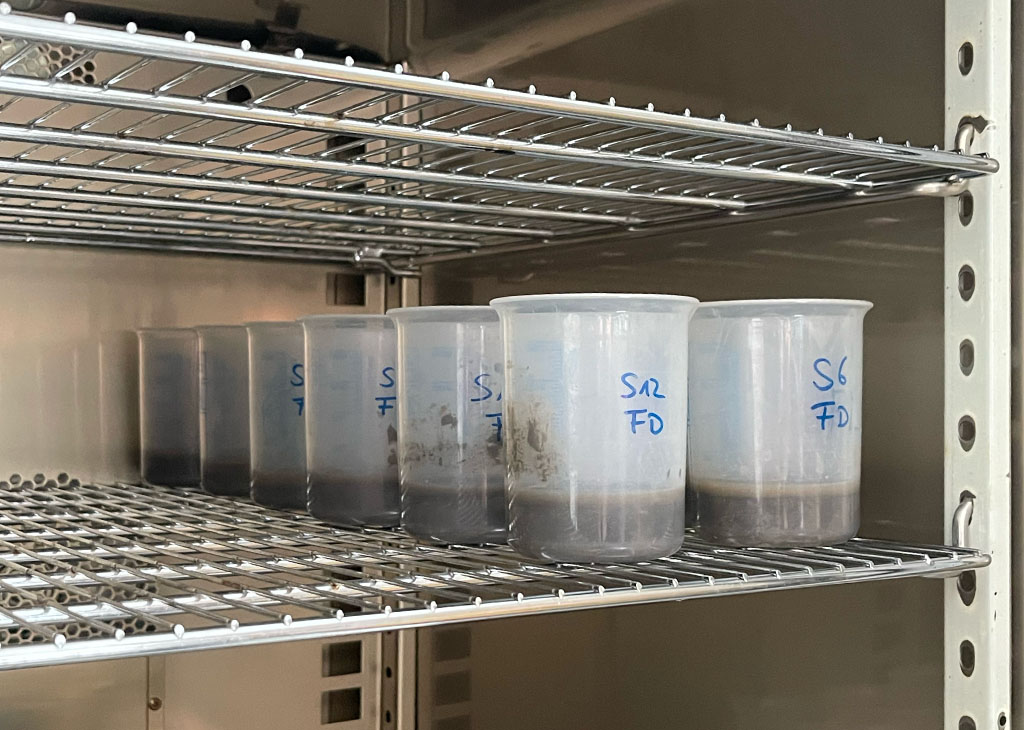

We focused on drilling ice-rich permafrost on the shoulders of ice wedge features in the polygonal terrain beside the braided river that runs through the valley. By the end of the day, we had collected 14 bagged core samples, which we analyzed in the cold lab (kept at -10°C) for the rest of the week.

It was such a special experience to physically interact with the permafrost I’ve spent so much time learning about. I’m incredibly grateful for this day in the field with my team and for the guidance from our amazing field instructors, Marjo and Knut. It’s a day I’ll never forget!

Wednesday: All-Day Presentation Prep

Wednesday was spent working on our presentations, pretty much all day long. It was intense but productive.

Thursday: Cold Lab Work and Burgers

Thursday was our first day working in the cold lab, cutting permafrost cores and making cryostratigraphic logs. After logging, we left the samples to thaw. The work was hands-on and fascinating, especially getting to see the layers in the cores up close. Later, we wrapped up the day with a group dinner where we made burgers—a highlight of the day.

Friday: Drying Samples

On Friday, we prepared our core samples by isolating them and putting them in the oven to dry out over the weekend after measuring the excess ice content in each. In the afternoon, we headed to Bjorndalen with Mark, a Quaternary geologist, who taught us about coastal erosion and the geologic history of Svalbard. It was a great way to tie everything together. Later that night, we celebrated with a bar tour of Longyearbyen. Sina and I had the most amazing bratwurst when we left Svalbar— I literally dreamt about it later that night.

Saturday: A Quiet Day by the Beach

I slept in late and then headed down to the beach on my own. I spent a couple of hours just sitting by the water, listening to music, and journaling. It was peaceful and gave me some much-needed time to reflect.

Sunday: Interview and Bonfire

On Sunday, I had an interview with Nastya about my journey as a geologist, how I transitioned to studying permafrost, and my dreams of becoming a planetary geologist. It was a thoughtful conversation that made me reflect on my path so far. That evening, we capped off the day with a bonfire on the beach.

Week 4

Monday: Analyzing Samples

We spent lunch on Monday analyzing our samples, diving into the data we’d collected from the previous week. It was a solid chance to really see what our work in the cold lab was yielding.

Tuesday: Glacier Fieldwork at Scott Turnerbreen

Tuesday was a long, but rewarding, day. We left UNIS at 8 a.m. and hiked about 16 km through the tundra, across a powerful river, and up rocky slopes. The route took us through a moraine and finally to two borehole sites in the glacier forefield at Scott Turnerbreen.

Once we arrived, we investigated a meltwater river and several small groundwater springs. We collected electrical conductivity (EC) measurements, determined the discharge of the river, and took oxygen isotope samples to figure out if the water was sourced from groundwater. It was an exhausting day but incredibly satisfying to work in such a dynamic glacial environment. At the end of our hike back, we stopped and wrote our names into the hiking log.

Wednesday: Presentation Prep

Wednesday was spent working on our presentations. Another full day of preparation, but it felt good to start pulling everything together.

Thursday: Boat Trip to the Lagoon Pingo

Thursday, we took a boat trip across the fjord to visit the famous lagoon pingo. We learned about the differences between geologic and microbial methane release in pingos and explored the various theories surrounding their formation. This deepened our understanding of how pingos are formed, the role of groundwater flow, and what makes them so unique. Gabby made the learning even more fun by building a makeshift plank to collect methane-rich water in a plastic bottle, hoping we could ignite the gas. Although we couldn’t get the match to light, the attempt at creating a fireball was memorable.

Friday: Presentation Day and Celebrations

Friday was presentation day, and the pressure was on. We were all a bit stressed, but in the end, we got through it! The sense of relief and accomplishment afterward was great. That evening, we celebrated with a group dinner at Kroa, where we were joined by Marjo, Knut, and Gabby. The reindeer steak with linden berries was divine; I did feel guilty eating the reindeer though. After dinner, we managed to convince them to join us at Maryanne’s for pool and darts—it was such a fun night. We enjoyed the sun together and celebrated the end of the course. Sina and I tried to get a bratwurst afterward, but they were sold out, so we had to settle for a potato instead.

Saturday

It was a sleepy day; I started on my proposal and cleaned my apartment.

Sunday: Pyramiden

Sunday was the most perfect day I spent in Svalbard. We left Elvesletta at 8 a.m., walking to the harbor for a boat excursion to Pyramiden. The weather was perfect. We spent the morning taking in the stunning views of bays, cliffs, and perfectly exposed outcrops, with puffins fishing in the water around us.

Lunch was grilled right on the boat—grilled ribs, sausage, fish, rice, and salad. It was delicious and just what we needed before we approached this massive glacier. The sheer size of it took my breath away. The cold air rolling off the glacier was so crisp and fresh; I couldn’t get enough of it. It’s incredible how alive the Arctic feels when you’re immersed in it.

Arriving in Pyramiden, we stepped into a surreal world where the Soviet flag still flew at the port. The town, abandoned in 1998, was like a time capsule. We explored the old dormitories (nicknamed "London" for the men and "Paris" for the women), and the cantina, which was lavish by any standard, with fabric wallpaper, an ornate staircase, and a fountain that, on holidays, once flowed with champagne. We saw the KGB office with its barred windows, the old mine, the northernmost Lenin statue overlooking the glacier, and the “Peace on Earth” sign from World War II carved into the mountainside where the coal mine once operated. The juxtaposition of that message in such a harsh, remote place really struck me.

One of the most beautiful stops was the swimming pool hall, with its stunning stained-glass windows and hand-carved wooden beams. The upstairs pool, though abandoned, still had this sense of grandeur with its intricate tiles and artwork. The cultural center, or “Kulturehouse,” was equally impressive, with its cinema, concert hall, library, gymnasium, and even the northernmost bar and gift shop! Our guide, Maggie, encouraged us to get "baptized" to become true polar men and women by taking a Soviet-style shot—so we were baptized at the top of the world!

Before heading back to the boat, we gathered for a group photo in front of the Pyramiden sign, and Sophia rolled me a cigarette as we sat and admired the glacier one last time. As we filed back on to the ship and started back across the fjord, the day already felt perfect, but then something unbelievable happened. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw a whale break the surface, and it was followed by more—an entire pod of beluga whales! I raced to the bow of the boat, my friends right behind me, and the whole ship fell silent. We watched in awe as a massive pod of beluga whales surrounded the boat. It was a symphony of white. It was utterly magnificent. I was so moved; I couldn’t hold back tears. Sophia came to stand beside me, and we just held each other, knowing this was the moment—the one I’ll remember forever when my mind returns to this summer.

The ride back was filled with laughter and more stunning views of the geology and sunlight. Along the way, we learned more about the history of the region—stories of explorers on their way to the North Pole, whalers, trappers, and some of the first women ever to step foot in Svalbard. Maggie shared her own story about coming here in the 1980s, inspired by a woman researcher from her small Swiss village. She had arrived with nothing but determination, stayed with a trapper, and never truly left. It was clear why this place had a way of pulling people in. By the time we returned, I was completely exhausted but overwhelmed with gratitude. I slept deeply that night, dreaming of whales.

Week 5

Monday

We left UNIS at 8 a.m. for our last AG-218 field trip, heading to Kapp Linne. The weather was rough—the wind was strong, and the sea was choppy. It was a bumpy two-hour ride, and by the time we finally reached the bay, I couldn’t feel my toes. It was so cold.

Once we arrived, we set off to explore the glacier lake formation, where we learned more about Svalbard’s geologic history. We had come from the sedimentary unit into the metamorphic zone, with 90-degree dipping beds. It was once believed these lakes were thermokarsts, but they’re groundwater springs sitting on top of karst rocks, with a complex, interconnected system between the springs. As we measured the electrical conductivity (EC) of the water, the ice sheet suddenly cracked with a sound like a gunshot. A few seconds later, we watched waves ripple from beneath the ice, making their way to the shore. It was incredible to witness.

We explored the vast polygonal ground and sorted circle terrain before hiking up the slope for a stunning view of the folded metamorphic beds. Then, it was time to head back to the boat. We suited up in our survival gear and got back on board for the ride home, which was much smoother this time. The sun had come out, and the fjord was bathed in beautiful light. As the boat carried us back from Kapp Linne, the fog lifted just enough for one last gaze of the glaciers that had become such a part of my life here. I knew in my heart that I was saying goodbye, not just to the landscape, but to a chapter of my life that had forever changed me. Svalbard was more than just a research trip —it was a place of growth, learning, and unforgettable beauty. I will miss AG-218. I will miss Svalbard. I will miss my friends. I will miss Marjo. I will miss UNIS. I will miss my apartment. I will miss my little life here.

Tuesday: A Relaxed Start

I slept in today and started cleaning and packing a little. The weather was beautiful, so I joined my friends for coffee. The sun was so *warm* (38°F) that I only needed a T-shirt. We sat on the steps of the café, soaking in the sunshine and enjoying each other’s company. After that, I spent the next nine hours working on my paper, writing 13 more postcards to friends and family, and smoking about eight cigarettes along the way to try and calm my nerves about the writing process. It was a mostly productive day.

Wednesday: Writing with Sophia

I spent the day cleaning my apartment and writing with Sophia, who came over for moral support. We had coffee and cigarettes and wrote for 7 hours. I sent out my postcards and picked up a birthday package from my dad, which was a nice surprise.

Thursday: Writing Marathon

Another day of intense writing, but this time, Sophia and I powered through and managed to finish our work just before midnight. We celebrated!

Friday: A Farewell to Svalbard

Friday was a whirlwind of packing, cleaning, and submitting my report. In the evening, I took one last plunge into the ocean with Nastya, Axel, Jorge, and Hannah— and though I knew it would be freezing, I wanted to make this moment meaningful. I pushed myself to stay in for as long as I could, counting to 150 in my head. The cold lit my skin on fire, but I wanted to feel every second of it. I wanted to remember this sensation, the way the water cleansed me. It felt like I was washing my soul in the heart of the Earth itself. This final plunge was a parting ritual, where I left a piece of myself in the water while taking something of Svalbard with me.

The rest of the night was spent enjoying my final hours in Svalbard before heading to the airport. It was an unbearably long day of travel ahead, but I tried to savor the last moments. Sina and Lisbeth saw me off at the bus station with one last bratwurst as a goodbye present. It was so hard to say goodbye to my friends. I kissed Sophia’s cheek and got on the bus with tears in my eyes; I wasn’t ready to leave, but it was time to go home. I flew with a few of the others from Longyearbyen until we split up in Oslo; it was so hard to say goodbye to everyone.

After 21 hours of flying, I landed in Houston 20 minutes before a hurricane touched down. I was so happy to have made it home safely.

To Conclude

As I reflect on my time in Svalbard, I am overwhelmed with gratitude. This experience has left an indelible mark on me. I’ve fallen in love with the Arctic—its raw beauty, its silence, and the powerful sense of isolation that made me feel more connected to the Earth than anywhere else. I’m already planning my return. There will always be an ‘after Svalbard’ in my life—a clear division between who I was before and the person I’ve become. This place has changed me. It has sparked something in me, pushing me to dream even bigger about exploring the world and embracing the unknown.

I’m the first in my lineage to have ventured this far north, and I wouldn’t have made it here without the unwavering support of my family, friends, professors, and the entire network of people who have loved and encouraged me along the way. I am a mosaic of all the people I’ve ever loved, and it’s love that has guided me to both the extraordinary and the everyday moments of my life. I’m beyond grateful for each of you and for all the incredible people I’ve met through AG-218. This experience has been transformative in more ways than I could have imagined, and I will carry it with me always.

Thank you, Svalbard, and thank you to everyone who has followed my journey.